- Home

- Harry Shannon

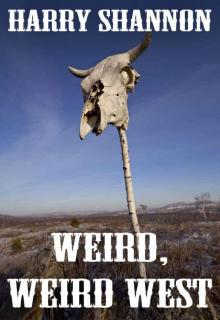

Weird, Weird West

Weird, Weird West Read online

WEIRD, WEIRD WEST

Short fiction by Harry Shannon

Copyright © 2011 Harry Shannon

These stories are works of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the authors' imaginations, or, if real, used fictitiously. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the author or publisher, except where permitted by law.

All Rights Reserved.

Table of Contents

The Name of the Wicked

Lucky

Them Bones

Blacktop

The Reckoning

Excerpt of CLAN

THE NAME OF THE WICKED

"The memory of the just is blessed;

But the name of the wicked shall rot."

Proverbs 10:7

How magnificent is the desert sky! The icy, scattered stars are like teardrops of crystal in a calm, dark ocean. A harsh wind is coming from the east, off the dry salt flats; wheezing down the gully and into this small canyon. It sounds like a creature in pain. Time hangs suspended. This land could effortlessly move a hundred years forward or back, but this is the night of April 16th, 1892.

Pray for me. I may not live to see the morning.

It's getting hard to think, much less write in this journal. I can no longer feel my legs and doubtless have lost a great deal of blood. I can't smell anything but dust, cordite, my own stink and the acrid odor of lamp oil. Ominous shadows are dancing all around me, lurking just beyond a yellow smear of light, waiting for my lantern to go out.

When the glare no longer hurts their eyes they will attack.

I have no excuse for my conduct; I certainly cannot plead ignorance. I returned to Nevada already well-schooled in the history of the region. After all, my grandfather's ranch, several miles south of Two Trees, overlapped much of what had been the land of the Horse Humans. I heard the legends at the knee of Nelly Tall Bear, who watched over me, this both before and after my parents died of the fever.

Old Nelly was a large woman, jolly yet quite imposing. She wore pale deerskin and turquoise beads that were patiently threaded onto tiny strips of leather: Oiled hair, black as newspaper ink; pulled back tight and braided. It kept her aging face youthful. In fact, Nelly still looked girlish much later, in her coffin. She told me of that savage tribe; how the Horse Humans had sacrificed their own children and young girls to a demon called Orunde. They were the only known cannibals in the region and eventually their bloodlust all but wiped them from the face of the earth.

As for me, I would tremble in awe when told of these primitive, horrible beings, my little pulse racing with boyish delight. On occasion my mother would overhear such a recitation, grow distraught and sternly admonish Nelly to 'stop this nonsense for the sake of the child's immortal soul.' Mother was a saved Christian and a stern taskmaster. I respected her, certainly, but it was Nelly whom I loved as my true mother. After such a scolding, Nelly would promise to refrain from speaking of the Horse Humans again, but before too long I would charm yet another tale from her reluctant lips.

On the other hand, my father was not a religious fellow. Indeed, he was known to enjoy the occasional card game, a cigar and some brandy. Father was a bald, round and bookish man given to wearing suspenders and wire-frame glasses. I think he found Nelly and her macabre fables quite amusing. In fact, he would argue to mother, 'would you rather he read a Grimm Brothers fairy tale of a cannibal witch baking live children in her oven?' Father reckoned that no harm could ever come to me merely from 'the fevered imagination of a tribe of illiterate savages.' Hogwash, he would sputter, is hogwash.

But Nelly swore that her own great-great-grandmother had been a Horse Human named Crow Wing. And that Crow Wing's mother, fearing for her life, sent her to the hills to live with the Cave People, because they worshipped the sky and seldom went to war. Then Crow Wing, knowing that the night of Orunde had come, sat high up in the mountains and watched the tiny fires in the valley. Only one child was to die. But this night the sacrifice spread like a blaze in dried sage; seeping out like blood upon the sand. The Horse Humans went berserk. Three children, four. Warrior turned on warrior. They skinned one another. More killed, more died. It was blood lust.

They say Crow Wing cried when she heard the final, tortured shrieks of the last remaining men, women and children. She vowed to tell the story; to pass it down from generation to generation, so that Orunde would never again successfully deceive a people. "Nelly, stop in the name of God!" Mother would cry. "Oh, hogwash!" Father would respond. "Let the boy be."

As previously stated, I was told these tales many times. They kept me hushed under the itchy covers, quaking but still, very long into the night; which is what I suspect old Nelly Tall Bear had intended. They also thrilled and disturbed me, thus sparking an interest in anthropology, anthropophagy and my wish to study at the finest schools in Europe after my parents passed on. Indeed, I did my Ph.D. on the legend of the Horse Humans, but Nelly would have been shocked, for I held that they had never truly existed. My thesis was that the tale of Orunde was apocryphal.

Hush!

A few pebbles zing merrily down a rock face and sprinkle a flat rock like jacks. Something is inching closer, staying just beyond the blush of yellow light. Tears spring to my eyes as I ache for opportunities lost and roads not taken.

Sweet Jesus, I am running out of time. Must hurry, write faster…

I returned to America via New York at the beginning of this year, 1892. I traveled west on the Union Pacific Railway, with my degree, boundless arrogance and a financial grant from the fine Territory of Nevada. I was determined to prove my thesis and write a scholarly book before achieving tenure at a suitably posh university.

In my arrogance, I had my life all mapped out. I returned to the Two Trees area via stage coach, I hired a digger; a merrily alcoholic sociopath named Abraham Lincoln Moon and ventured out into the desert on horseback.

My deceased grandfather's ranch had been sold whilst I was abroad, of course; various parcels had then been divided and auctioned away to pay taxes. I had not been home in many years, although I knew that the area I wanted to visit lay a few miles south. Research had revealed that the deed was held by one Samuel Moon, the uncle of my drunken assistant, a fact which explains the necessity of his foul presence. He sang, mumbled and was exceedingly flatulent the entire trip.

We rode further into the sage-freckled emptiness of the Nevada desert, until all signs of civilization vanished. No telephone poles, railway tracks, fences; not so much as a strand of barbed wire, (as a child I had called the wickedly spun metal twine 'bob wire'). The heat was as scorching as I remembered.

The day dragged by until finally a red sunset stained the horizon. We had ridden for several miles when we spotted some cow skulls and buzzard feathers near a huge mound of earth. Abe Lincoln took a long drink of whiskey, belched and shook his head. "There," he said. "That was the Horse Human land."

"And you're uncle Samuel lives there?"

"No."

"Excuse me?"

"Not lives. He watches."

"Watches what?"

Abe Lincoln Moon shrugged. "Just watches."

We continued on. My buttocks and thighs ached mightily and it was dusk by the time we located the dilapidated wooden shack. It had splintered frame windows and a roof of dented sheet metal that arched like a rainbow in the pastel sunset. I squinted and made a note in this journal as Abe Lincoln Moon approached the house.

"Empty."

I shivered. The night was cool; a dry breeze raised the small hairs on my neck. I took a drink of w

ater and swatted a horse fly away from my reddened nose. "Perhaps he is sleeping," I ventured.

Abe Lincoln scowled again. He grunted. "I doubt it."

For some reason his stereotypical behavior annoyed me. I slid down from my mount and cringed. I was used to traveling in a buckboard or a carriage. My very testicles hurt. I had not ridden a horse in many a year. I massaged my muscles beneath the stiff new work pants.

"We'll camp here," I said, imperiously. "I don't give a damn if your uncle is home or not. My buttocks are sore and I need something to eat. Build a fire."

Abe Lincoln Moon said: "Build your own."

I blinked. "Excuse me?"

He shook his head again. "I won't," he said. "Not on this ground. This ground is sacred."

I squatted down and rubbed my eyes. I fear I was quite condescending. "Mr. Moon," I said, "it's getting late and I am weary. Now, first of all the entire Horse Human legend is just that, a legend. I have already told you that. There is nothing here that will harm us. Second, your uncle has built his home here, so quite obviously this place is safe. Third, if it is a question of money, I can…"

Moon snorted. "You think I am not afraid because it is Horse Human land?" He slapped his own chest. "I have their blood in me." I rolled my eyes, but he did not seem to notice. "But this is also where many white men are buried. That makes for too much magic."

Moon now seemed totally sober and somewhat imposing. In fact, his doughy facial features had somehow hardened. He now reminded me of Nelly Tall Bear, my beloved childhood nanny. I swallowed and jumped to my feet. "White people?" I looked around, and my heart kicked in my chest. Even at dusk it became clear to me. I registered the scoured, white rock face and the Two Trees; the low creek bed and the gully coming in off the flats. "My God," I said. "This was part of my grandfather's property, Moon! I remember it from when I was a boy. Your uncle took some of the land nearest our spread."

"Yes."

"Members of my family were buried near here. How wonderful! In fact, I may see their graves again soon, after all this time!"

Moon was silent. I could see he was troubled, but I cared not. I twirled in circles, like a child in a circus tent for the very first time, eyeing the rock face above. "But where is the house my grandfather constructed?" I cried. "It was of a decent size, and mainly built of stone."

Then I remembered the sadness of my parent's passing, and that all those who had lived here were now passed away and gone. My enthusiasm waned. A long moment passed. I repeated myself: "Where is that house?"

"Torn down, brick by brick," Moon said.

"No! But why?"

Moon spat onto the parched earth. "To calm the spirits," he said. "You may think I'm foolish, but they wished things…repaired. Back the way they were before the white men came."

A chill ran through me. "They wanted?"

Moon smiled white and wide, but now his eyes were flat, reptilian slits. "I don't have an Uncle Samuel," Moon said. "Not any more. He died five winters ago."

"But…"

Moon looked up and around. Shadows were streaming out of the mountains like stalks from a carnivorous plant. He casually pulled a long Army Colt pistol and aimed it at my lower belly. I am ashamed to say that my bladder released.

"Step back, sir," Moon said. "Get away from the animal."

I did as I was ordered.

In a flash, Moon was on his horse, clicking with his tongue and leading my mount away. I watched him go, my throat tight with terror. Fortunately, I had my canteen in one hand and my own hand gun tucked into the back of my leather belt. I dared not draw it. Mr. Moon would have surely cut me down had I tried.

"Where are you going?" I cried weakly. "What shall become of me?"

"Truth is, I don't know."

Moon looked back over his shoulder only once, and again I was struck by how different he seemed. With the palate of sunset behind him he seemed like a brave warrior from bygone days. I half expected to see feathers in his hair.

"Why are you doing this?"

"Because of your family, sir. Your family desecrated this ground," Moon said. He spoke softly, yet my belly flooded with adrenaline. "And because the Horse Humans are buried here," he continued. "Nothing personal, but they need to stay buried."

"Moon!"

But at once my guide vanished over the horizon, horse hooves clopping on scattered rocks; my needed mount in tow. It was night. I was alone in the wilderness with a handgun, six bullets and half a canteen of water. I struggled to control my consternation. I circled the small area, looking for ideas. The shed was nearly worthless, but would serve as some kind of shelter were I to arrange the components properly. I found the lantern, a moldy box of matches and a small container of oil. I dragged the sheet metal over to a dead-end section of the gully and propped it up on opposite lips of sand. I braced it with timber and stepped back. Now I would have three sides blocked and only one open.

It was totally dark in the canyon and the wind was rising.

Something howled, and my skin crawled like a colony of black ants. Coyotes? Likely nothing to be afraid of, and yet I felt an atavistic dread beyond description. I wasted four of the precious matches before I succeeded in lighting the lamp. The yellowed expanse of brightness warmed my very soul. I paced the area, trying to hold the terrain in my mind. I am an anthropologist, and I know the deep and ghastly dread of the darkness that lives in the bravest of men. I wanted to defend myself with logic, awareness and perhaps even to sketch a small map so that I would be able to readily picture the area around me during the night. For a moment, I felt I had control of the situation.

There came a fiendish grunt. I froze and then spun around, holding up the lantern, gasping rapidly for air…nothing. But then I heard a liquid slurp, like a large beast slavering and sucking up its own drool. I drew my weapon. My hand trembled. I backed away, towards my cubby hole in the parched earth, my chest tight and my face slick with sweat.

The first one came from the south.

It shambled sideways, something like a sea crab. I cringed back and gasped. At first I thought it to be some prehistoric being returned from the bed of a dried-up sea. But it was worse than that, far worse. It was something that had once been human. The hair and nails were impossibly long, and rags still clung to the clicking bones. Some skin still stretched across the skull like yellowing parchment, and one cheek had been eaten away, likely by insects. The hideously grinning teeth shone through like yellowed piano keys. They opened and closed with an audible clack.

I fired, but it did not flinch. I fired two more times and it stopped. Then the thing emitted a small, high-pitched squeal and retreated into the darkness. I swallowed vomit and thanked God for my luck, for I must have struck some remaining vital area. I was down to three bullets. I backed away and started to duck down into my make-shift home at the foot of the gully. The creature scuttled forward again.

I heard a low, urgent moan of unholy desire from behind me, and knew there were others. I spun and fired twice, wasting more precious bullets. Then I crawled into my hole and curled up in a ball. To my utter horror I heard many more of the things approaching; and now from all directions. Whistles, shrieks and coughs ensured. They were dead, yet had voices of some kind, but from what soulless, fleshless orifice those sounds were created I do not know. I had but two bullets remaining in my side arm, and knew that my hubris was to cost me my life.

I drank some tepid water. I closed my eyes and prayed. When I opened them again, a thing beyond description faced me. It stood just at the edge of the light. He had long white hair and filthy nails; an eviscerated rodent hung from a clenched fist. His ravaged features were tilted to one side in a quizzical manner. A long, thin string of bloody drool hung from the jawbone and trailed off into the sand. He wore what remained of a black suit with tails.

Something happened inside me, something I cannot explain. In a flash I recalled my grandfather's funeral, his distinguished body packed in ice for the wake; and the black suit with

tails he had been buried in. Could such a thing be? I felt the strangest mixture of fascination and sickly dread. I raised the lantern and inched as close to the monster as I dared.

The grandfather thing retreated, and it was then I realized my bullets had been useless. However, they were afraid of the light! I moved forward, and after taking a deep breath, stepped out into the gully. The yellowish glow spread. It beat back the night. All around me, gnarled forms withdrew; hissing their disappointment.

"Grandfather?"

The thing cocked its head again, as if responding to my voice with invisible ears. I swallowed more bile and stepped forward. "Can you help me…?" And at once I heard movement behind me, as several of the things attempted to slip down into my shelter. I whirled around and fired without thinking.

One bullet left.

I raised the light. The creatures grumbled and stumbled; cawed, crawled and staggered away. Now I could see that some were male, some female; some large and some mere children. Many wore what had once been the clothing of white settlers. Some wore fragments of tribal garments or carried ancient weapons. In this horrid place, the dead continued on indefinitely.

My breath left me and the world fell away. "Help me, Jesus."

I saw them clearly, a few yards off: The same long hair and nails; all bones and strips of filthy fabric. They were fighting, as usual, only now over something red and wet. My father, improbably wearing bent wire rim glasses and what remained of his gold suspenders, was snarling and clawing at a raw, purple-veined chunk of meat. Meanwhile, my mother tried to drive him off by striking him with her well-worn Bible. They had become a ghastly and grotesque parody of themselves. I lowered the lamp in disgust.

Movement behind me! My body was now blocking out the light. The grandfather thing lurched forward and teeth sank into my lower leg. The pain was excruciating and I made a sound so high and shrill it could have come from a woman. I kicked out and pulled away, but the predator would not release me.

Dark Thoughts

Dark Thoughts CLAN

CLAN One of the Wicked: A Mick Callahan Novel

One of the Wicked: A Mick Callahan Novel Eye of the Burning Man: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Series)

Eye of the Burning Man: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Series) Pain

Pain Weird, Weird West

Weird, Weird West Running Cold (The Mick Callahan Novels)

Running Cold (The Mick Callahan Novels) Memorial Day: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Novels)

Memorial Day: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Novels) Behold the Child

Behold the Child Night of the Beast

Night of the Beast The Pressure of Darkness

The Pressure of Darkness Daemon: Night of the Daemon

Daemon: Night of the Daemon A Host of Shadows

A Host of Shadows Kill Them All

Kill Them All